Monthly Archives: May 2011

The places in between

There are those who believe that technology has hijacked the whole of the visitable earth, snatched it away, miniaturised and simplified it, making travel so accessible on a flickering computer screen that there is no need to go anywhere except to your room. In a related way, the travel book is believed to have been not just diminished but made irrelevant by the same technology. Since we know everything – the information is easily dialled up – and the world has been so thoroughly winnowed by travellers, what is the use of a travel book? Where on earth would you go to remark each anxious toil, each eager strife, or watch the busy scenes of crowded life? Surely it has all been written.

This isn’t a new conjecture. In 1972, in a blasé magazine piece of postmodernism, entitled “Project for a Trip to China”, the American writer Susan Sontag sat in her New York apartment ruminating on China. Sontag was that singular pedant, a theorist of travel rather than a traveller. She concluded her piece: “Perhaps I will write the book about my trip to China before I go.”

To such complacent and lazy minds, here is a suggestion. Try Mecca. After prudently having himself circumcised, learning to speak fluent Arabic, dressing as an Afghan dervish and calling himself Mirza Abdullah, the British explorer Sir Richard Burton travelled to the holy city of Mecca, a deeply curious unbeliever among devout pilgrims. This was in 1853. He published his account of this trip in three volumes several years later, his Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah and Meccah. The last non-Muslim to do this and to write about it was Arthur John Wavell, of the distinguished British military family. An army veteran, and farmer in Mombasa, Kenya, Wavell developed an interest in Islam. In order to know more, he disguised himself as a Swahili-speaking Zanzibari, made the pilgrimage and wrote about it in A Modern Pilgrim in Mecca (1912). Wavell took the trip in the winter of 1908-1909, more than a century ago. No unbeliever has done it since. Now there’s a challenge for a technology-smug couch potato who prates that the travel book is over. Of course, this daring trip is not easy. It is, perhaps, not a journey for a gap-year student wishing to make his or her mark as a travel writer but it is a book I would want to read.

Studying Housing Through Distorted Indexes

There is some reason, however, to think that the recent price declines may be overstated by the index. The figures are based on sales of the same home over time, but there is no way to measure changes in the quality of a home.

With many homes now being sold in distress, either because of foreclosure or as “short sales” in which the sales price is below the amount owed and all the proceeds go to the lender, it is likely that some of the homes were in poor condition. In addition, such sales are often made for lower prices than comparable homes could obtain if sold without time pressures. If and when nondistress sales become a larger part of the market, that could cause the index to rise even if the overall market is not getting stronger.

Lessons from war’s factory floor

The lowest point of the US occupation of Iraq was about five years ago. American forces had no effective strategy in the face of a street-level civil war and a particularly vicious insurgent group, al-Qaeda in Iraq. At Haditha, frightened and frustrated marines had killed 24 civilians. At Samarra, the Golden Dome mosque had been destroyed – a potent symbol of conflict between Shia and Sunni Muslims. Donald Rumsfeld, then defence secretary, appeared to be in an advanced state of denial, breezily waving away good advice, and in a notorious press conference shortly after the atrocity at Haditha, refusing to use the word “insurgent”, or to let the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff use it either. The US strategy was failing and its leadership was determined not to change direction. It was a case study in organisational dysfunction.

Yet by 2008, the situation in Iraq had improved radically. Al-Qaeda in Iraq was in retreat, and the number of attacks, American and Iraqi deaths had fallen dramatically. Although the success remains fragile and there were other factors involved, a complete transformation of US military strategy deserves much credit.

How did it happen and what are the lessons for other organisations that need to turn around? The easy answer is that the solution was a change of leadership. Thanks to behind-the-scenes campaigning and a drubbing in the midterm elections for President George W.?Bush, Mr Rumsfeld was replaced, and General David Petraeus was put in charge of the war in Iraq.

Henry Kissinger talks to Simon Schama

Not so much, though, as to get in the way of treating China as an indispensable element in any stabilisation of perilous situations in Korea and Afghanistan. Without China’s active participation, any attempts to immunise Afghanistan against terrorism would be futile. This may be a tall order, since the Russians and the Chinese are getting a “free ride” on US engagement, which contains the jihadism which in central Asia and Xinjiang threatens their own security. So was it, in retrospect, a good idea for Barack Obama to have announced that this coming July will see the beginning of a military drawdown? The question triggers a Vietnam flashback. “I know from personal experience that once you start a drawdown, the road from there is inexorable. I never found an answer when Le Duc Tho was taunting me in the negotiations that if you could not handle Vietnam with half-a-million people, what makes you think you can end it with progressively fewer? We found ourselves in a position where to maintain … a free choice for the population in South Vietnam … we had to keep withdrawing troops, thereby reducing the incentive for the very negotiations in which I was engaged. We will find the same challenge in Afghanistan. I wrote a memorandum to Nixon which said that in the beginning of the withdrawal it will be like salted peanuts; the more you eat, the more you want.”

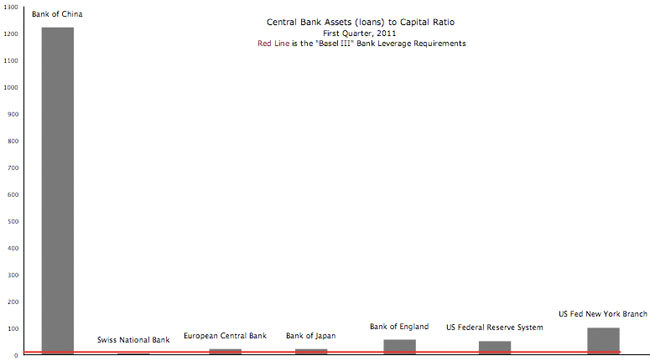

Investing, Risk, Politics & Taxes: Global Central Bank Leverage

Source: Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, 5/20/2011 edition. Worth considering for financial & risk planning.

Related: Britannica: Central Banks and currency.

Basell III details: Clusty.com and Blekko.

More of God’s Floral Handiwork

In-N-Out vs. Five Guys vs. Shake Shack: The First Bi-Coastal Side-By-Side Taste Test

Anyone who moves around in burgercentric circles knows of the battle that’s been brewing for the last few years between the three major heavyweights of the high-quality fast-food burger* world. Of the three, In-N-Out Burger, founded in Baldwin Park, California, in 1948 has the longest history and certainly the most cult-like and devout following. On the other hand, Virginia’s Five Guys–which has been around since 1986–has seen crazy expansion in the last few years, now boasting over 750 locations on both coast and a rabid following that is fast catching up on In-N-Out’s heels. The underdog in the fight is New York’s Shake Shack. Only seven years old, it’s still a baby in the field, but if we’re to believe the news, they’re poised to expand, and in a big way (they just opened their latest location in Washington, D.C. yesterday).

But who really makes the best burger? It’s a question that’s debated far and wide on the internet and beyond, so we here at A Hamburger Today decided to take it upon ourselves to find the answer and declare an official King of the High Quality Fast Food Burger.

Former Fed Vice Chair: Kohn ‘regrets’ pain of millions in financial crisis

The former vice-chairman of the Federal Reserve has said he “deeply regretted” the pain caused to millions of people around the world from the financial crisis, admitting that “the cops weren’t on the beat”.

Don Kohn’s apology for the actions of Federal Reserve in the run-up to the financial and economic crisis goes significantly further than the limited responsibility taken by his former boss, Alan Greenspan.

Speaking to British MPs at a confirmation hearing on Tuesday, Mr Kohn nevertheless said his experience would be valuable for the Bank of England, where he has been appointed to a new committee with powers to guide UK financial stability.

“I believe I will not make the same mistake twice,” he said.

Mr Kohn has been appointed to the Bank’s new Financial Policy Committee, which will soon have powers to change system-wide UK financial regulations and even limit borrowing by households and companies if it thinks there are threats to financial stability.

Having been a strong advocate of the Greenspan doctrine not to burst asset bubbles but to mop up any mess after a crash, Mr Kohn recanted much of his previous view in front of MPs. He said he had “learnt quite a few lessons – unfortunately” from the financial crisis, including that people in markets can get excessively relaxed about risk, that risks are not distributed evenly throughout the financial system, that incentives matter even more than he thought and transparency is more important than he thought.

An Interview with Platon

FEW photographers find themselves grasping Mahmoud Ahmadinejad by the hand, facing down Robert Mugabe or eliciting a grin from Binyamin Netanyahu–all within a 72-hour period, no less. Platon, a London-raised and New York-based photographer, is the keen eye behind “Power: Portraits of World Leaders” (Chronicle Books), a book of 150 photographs of world leaders, all of them taken at the United Nations.

This collection is full of surprises and affirmations alike: Hugo Chávez has all the penetrability of an Easter Island statue; Victor Yushchenko could be a friendly school principal; and Muammar Qaddafi is a villain straight out of “Star Wars”. Securing the portraits required tenacity, quick reflexes and the wiles of a fixer. More Intelligent Life spoke with Platon, a staff photographer at the New Yorker, about his adventures in assembling his portraits.