Three weeks ago my wife and I flew China Eastern from Beijing to Shanghai and, thanks to traffic miracles on both ends and the absence of the usual Beijing departure hold, made it door-to-door in about four hours.

Today I flew US Airlines from Washington to Boston, a more-or-less comparable route, in just about the same door-to-door time. One difference: Beijing-Shanghai is more than half again as far (576 nautical miles, vs. 343). Another: often I’ve been loaded onto a 747 for the Chinese route, versus the Airbus 319 that is standard for US Air. But here’s the general compare/contrast rundown:

The Subprime Collapse Didn’t Start Bothering the Bush Administration until Wall Street Bankers Started Whimpering

When individual borrowers began to suffer, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke and Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson didn’t seem overly concerned. The market would clear out the problem through the foreclosure process. Loans would get written off; properties would change hands and be resold. When upstart subprime mortgage lenders ran into trouble, Bernanke and Paulson shrugged again. The market would clear out the problem through the bankruptcy process. Subprime companies like New Century Financial filed for Chapter 11, others liquidated or restructured, and loans made to the lenders were written down. Meanwhile, Paulson and Bernanke assured us that the subprime mess was contained.

But as the summer turned to fall, and the next several shoes dropped, their attitude changed. And that is because the next group of unfortunates to fall victim to subprime woes were massive banks. In recent years, banks in New York, London, and other financial capitals set up off-balance-sheet funding vehicles called SIVs, or conduits. The entities borrow money at low interest rates for short periods, say 30 to 90 days, and use the funds to buy longer-term debt that pays higher interest rates. To stay in business, the conduits must continually roll over the short-term debt. But as they searched for higher yields, some conduits stuffed themselves with subprime-mortgage-backed securities. And when lenders became alarmed at the declining value of those holdings, they were reluctant to roll over the debt. Banks thus faced a choice. They could either raise cash by dumping the already-depressed subprime junk onto the market, or bring the conduits onto their balance sheets and assure short-term lenders they’d get paid back.

Related: Credit Risk is Rising Again.

Morning Workout Zeitgeist, or “Let’s turn the Capitol into a Casino/Waterpark”

Props to the early morning workout group for this inspiration.

“Spoiled Tuna”

Have you noticed how even Presidential races have now been reduced to dollar figures? I don’t mean the effect that money has on shaping political agendas and voter perceptions – this has been going on since at least the time of Pericles. I am referring instead to the assessment of candidates’ appeal to voters based on how much money they have raised in their election “war chests”. Hillary is deemed to be the frontrunner because she has raised X million dollars more than Barack, who is ahead of John Edwards and so on and so forth. This is so much like the order book of an IPO (initial public offering), for chrissakes. The more orders that flow in during the book-building period the better the chances that the issue will be “hot” and open for trading at an immediate premium. Hillarydotcom and Barrackdotcom.

The Billionaire Who Wasnt: How Chuck Feeney Made and Gave Away a Fortune Without Anyone Knowing

In 1988 Forbes Magazine hailed Chuck Feeney as the twenty-third richest American alive. Born in Elizabeth, New Jersey to a blue-collar Irish-American family during the Depression, a veteran of the Korean War, he had made a fortune as founder of Duty Free Shoppers, the world’s largest duty-free retail chain. But secretly, Feeney had already transferred all his wealth to his foundation, Atlantic Philanthropies. Only in 1997, when he sold his duty free interests, was he “outed” as one of the greatest and most mysterious American philanthropists in modern times. A frugal man who travels economy class and does not own a house or a car, Feeney then went “underground” again, until he decided in 2005 to cooperate in a biography to promote giving-while-living. Now in his mid-seventies, he is determined his foundation should spend the remaining $4 billion in his lifetime. The Billionaire Who Wasn’t is a tale of one of the greatest untold retail triumphs of the twentieth century, and of what happens to a unique man and his family when confronted with wealth beyond imagining.

Tax avoidance is the flip side to Mr Feeney’s philanthropic coin. He is addicted to it. “Chuck hates taxes. He believes people can do more with money than governments can,” says a friend. In 1964 a young New York lawyer, Harvey Dale, told Mr Feeney that changes in the tax laws threatened his business, which was running risks that could put the founders in jail. On his advice, Mr Feeney and his co-founder, Robert Miller, transferred ownership to their foreign-born wives, from France and Ecuador, respectively.

In 1974, through a deal with the American government, the firm turned the Pacific island of Saipan into a tax haven. Then, in 1978, Mr Feeney grouped his various investments, including his shares of DFS, in a holding company, General Atlantic Group Limited, in tax-free Bermuda. To escape the American taxman, everything was still registered in his wife’s name.

Mr Feeney carefully shunned all outward evidence of wealth. But as soon as DFS became reliably profitable, he started the practice of giving 5% of his pre-tax profits to good causes. In 1982 he created a foundation, the Atlantic Philanthropies, based in Bermuda. Two years later he signed over his fortune to the foundation, except for sums set aside for his wife and children. His net worth fell below $5m. When he broke the news to his children, he gave them each a copy of Andrew Carnegie’s essay on wealth, written in 188

Pre-Movie Theatre Ads Now $450M Business

In-theater ads hit $456 million in 2006, up 15% from 2005, says the Post, citing a report by the Cinema Advertising Council. For perspective, this is about the size of Viacom’s “digital” revenue. The head of the council, Cliff Marks, who also happens to be head of sales for the public play in the sector, National Cine-Media (NCMI, see below), says that the introduction of digital projectors is helping spur adoption, as advertisers no longer have to burn ads onto film.

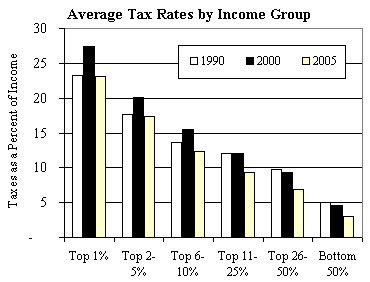

Average US Income Tax Rates

Greg Mankiw. It would be interesting to see a more detailed analysis of this.

Ciudad de las Artes y las Ciencias

James Duncan Davidson. Calatrava

On Political Correctness

Nobel Prize Winner Doris Lessing:

WHILE we have seen the apparent death of Communism, ways of thinking that were either born under Communism or strengthened by Communism still govern our lives. Not all of them are as immediately evident as a legacy of Communism as political correctness.

The first point: language. It is not a new thought that Communism debased language and, with language, thought. There is a Communist jargon recognizable after a single sentence. Few people in Europe have not joked in their time about “concrete steps,” “contradictions,” “the interpenetration of opposites,” and the rest.

The first time I saw that mind-deadening slogans had the power to take wing and fly far from their origins was in the 1950s when I read an article in The Times of London and saw them in use. “The demo last Saturday was irrefutable proof that the concrete situation…” Words confined to the left as corralled animals had passed into general use and, with them, ideas. One might read whole articles in the conservative and liberal press that were Marxist, but the writers did not know it. But there is an aspect of this heritage that is much harder to see.

Even five, six years ago, Izvestia, Pravda and a thousand other Communist papers were written in a language that seemed designed to fill up as much space as possible without actually saying anything. Because, of course, it was dangerous to take up positions that might have to be defended. Now all these newspapers have rediscovered the use of language. But the heritage of dead and empty language these days is to be found in academia, and particularly in some areas of sociology and psychology.

On Political Corruption

Larry Lessig turns his attention to political corruption. Video. Well worth watching.