The legal dispute between Apple and the FBI might prove pivotal in the long-running battle to protect users’ privacy and right to use uncompromised encryption. The case has captured the public imagination. Of course, EFF supports Apple’s efforts to protect its users.

The case is complicated technically, and there is a lot of misinformation and speculation. This post will offer a technical overview, based on information gleaned from the FBI’s court motion and Apple’s security documentation.

What is Apple being asked to do?

Apple is being asked to assist the FBI’s ongoing investigation of last December’s San Bernardino mass shooting by providing software to unlock a phone used by (deceased) suspect Syed Rizwan Farook (though owned by his employer, the San Bernardino County Department of Public Health). Legally, the FBI is citing the All Writs Act, a general-purpose law first enacted in 1789 that can allow a court to require third parties’ assistance to execute a prior order of the court when “necessary or appropriate.” Judges have questioned the application of this general purpose law for unlocking phones.

Monthly Archives: February 2016

Sun, Sea, Stars and Seclusion: Hotel Molokai

Molokai Museum and Cultural Center (adjacent to the R.W. Meyer Sugar Mill).

Purdy’s Natural Macadamia Nuts.

Finally, I heard a beautiful rendition of “Praise God from Whom All Blessings Flow” on Molokai.

Tuesday morning music, Molokai

Daily verse, via notifications on your Watch, iPhone and iPad.

The Revolving Door from the Pentagon to the Private Sector

Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington:

This report and short video, released in partnership with Brave New Foundation, reveal the extent of the Pentagon’s revolving door phenomenon, in which retired high-ranking generals and admirals cash in on their years of military experience by taking lucrative jobs with the defense industry.

CREW found 70 percent of the 108 three-and-four star generals and admirals who retired between 2009 and 2011 took jobs with defense contractors or consultants. In at least a few cases, these retirees have continued to advise the Department of Defense — all while on the payroll of the defense industry.

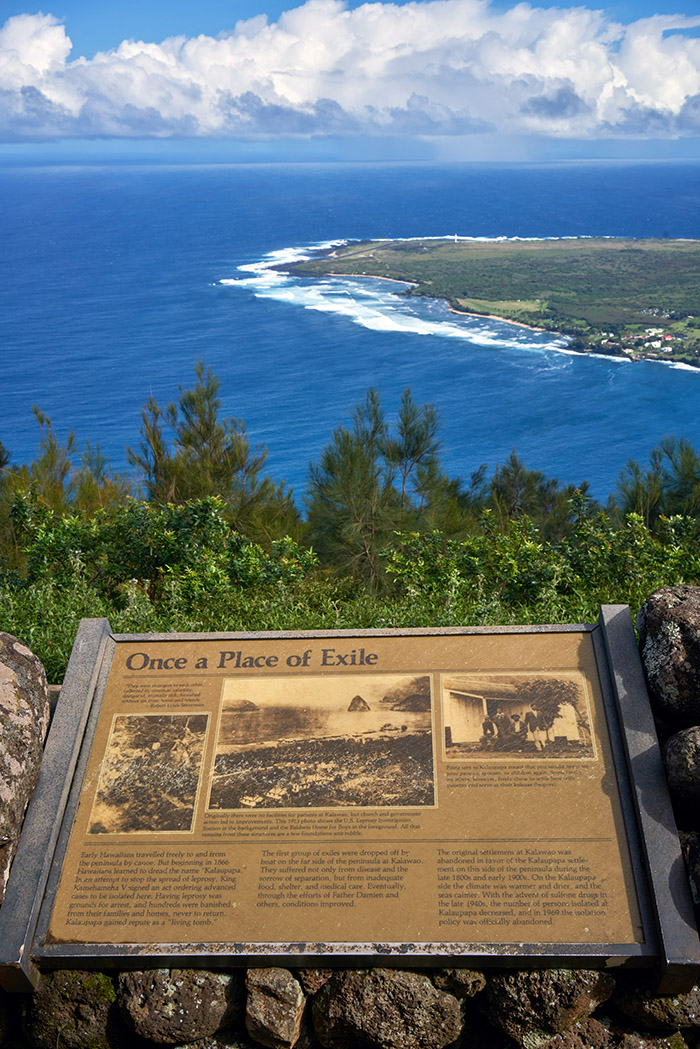

Gazing at Kalaupapa

Wikipedia on Molokai.

When the Last Patient Dies by Alia Wong

Not so long ago, people in Hawaii who were diagnosed with leprosy were exiled to an isolated peninsula attached to one of the tiniest and least-populated islands. Details on the history of the colony—known as Kalaupapa—for leprosy patients are murky: Fewer than 1,000 of the tombstones that span across the village’s various cemeteries are marked, many of them having succumbed to weather damage or invasive vegetation. A few have been nearly devoured by trees. But records suggest that at least 8,000 individuals were forcibly removed from their families and relocated to Kalaupapa over a century starting in the 1860s. Almost all of them were Native Hawaiian.

Sixteen of those patients, ages 73 to 92, are still alive. They include six who remain in Kalaupapa voluntarily as full-time residents, even though the quarantine was lifted in 1969—a decade after Hawaii became a state and more than two decades after drugs were developed to treat leprosy, today known as Hansen’s disease. The experience of being exiled was traumatic, as was the heartbreak of abandonment, for both the patients themselves and their family members. Kalaupapa is secluded by towering, treacherous sea cliffs from the rest of Molokai—an island with zero traffic lights that takes pride in its rural seclusion—and accessing it to this day remains difficult. Tourists typically arrive via mule. So why didn’t every remaining patient embrace the new freedom? Why didn’t everyone reconnect with loved ones and revel in the conveniences of civilization? Many of Kalaupapa’s patients forged paradoxical bonds with their isolated world. Many couldn’t bear to leave it. It was “the counterintuitive twinning of loneliness and community,” wrote The New York Times in 2008. “All that dying and all of that living.”

The Wintergarten: Lunch @ Kaufhaus des Westens (KaDeWe) Berlin

Soccer fans from Dortmund and Wolfsburg were in abundance at the impressive Wintergarten.

Pipiwai Trail to Waimoku Falls Panorama

Berlin

Traveler

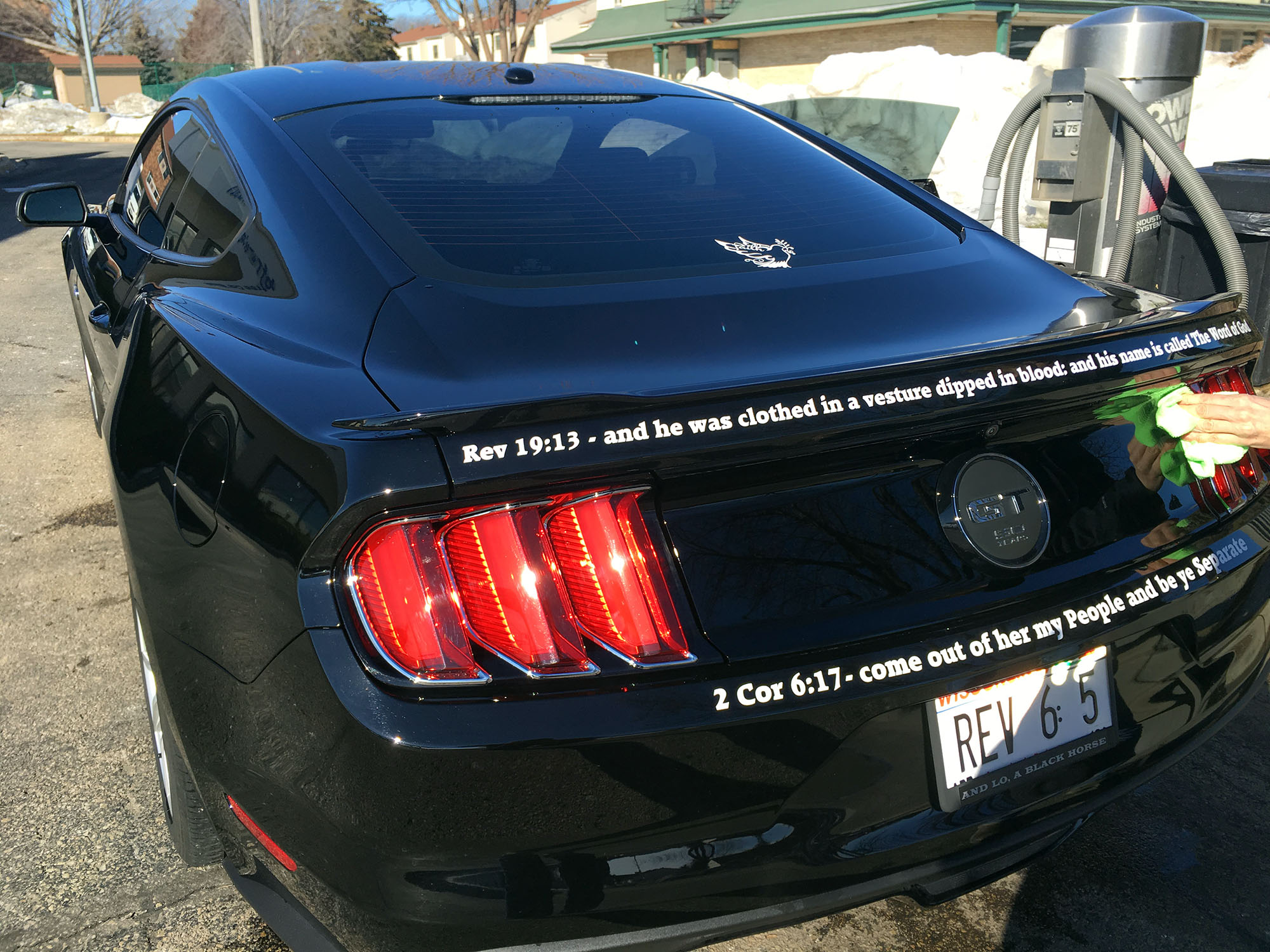

Revelation and a Black Mustang

Surely old fashioned, yet biweekly, I check the tire pressure on our cars. This being winter, the tires in question are blizzaks.

My club – those who check their tires – is not large [1]. Yet, it is the interloper that is most satisfying.

Recently, it was a fuel truck driver, shivering while disgorging petrol into the nearby underground tanks. He inquired after the reliability and utility of our late model Subaru. I shared positive words, but for the two recalls and a recent hood latch annoyance.

Diving further into autodom, we agreed on the pleasures of German cars as he described two: a VW and BMW. News of his Munich V-8 maintenance costs “we were driving into Chicago….”, included a rather lengthy sigh.

Today’s encounter was deeper and unusually spiritual. Glancing skyward from my pressure gauge, a jet black Ford Mustang gleamed in the afternoon sun. Its owner vigorously wiping fresh soap residue away.

There was more. Fonts and text. Words on the trunk and bumper. A vanity license plate. A sticker facing followers.

I inquired about the car and verses. Why a Mustang?

“It represents Revelation’s black horse, spiritual famine”.

Fascinating.

The two verses featured on her black Mustang are:

Revelation 19:13 [New International King James Martin Luther Commentary]

2 Corinthians 6:17 [New International King James Martin Luther Commentary]

Vanity Plate: Revelation 6:5 [New International King James]

Those interested in a daily verse (5 languages and notifications) might try the new My Verse app.

[1] Tire Pressure Special Study.

[2] 2015 Ford Mustang CAR Magazine and duck duck go

Easy feels true: on surveys

Surveys are the most dangerous research tool?—?misunderstood and misused. They frequently straddle the qualitative and quantitative, and at their worst represent the worst of both.

In tort law the attractive nuisance doctrine refers to a hazardous object likely to attract those who are unable to appreciate the risk posed by the object. In the world of design research, surveys can be just such a nuisance.

Easy Feels True

It is too easy to run a survey. That is why surveys are so dangerous. They are so easy to create and so easy to distribute, and the results are so easy to tally. And our poor human brains are such that information that is easier for us to process and comprehend feels more true. This is our cognitive bias. This ease makes survey results feel true and valid, no matter how false and misleading. And that ease is hard to argue with.