I have long enjoyed taking sports photos, particularly those of our children along with their friends, teammates and from time to time, competitors.

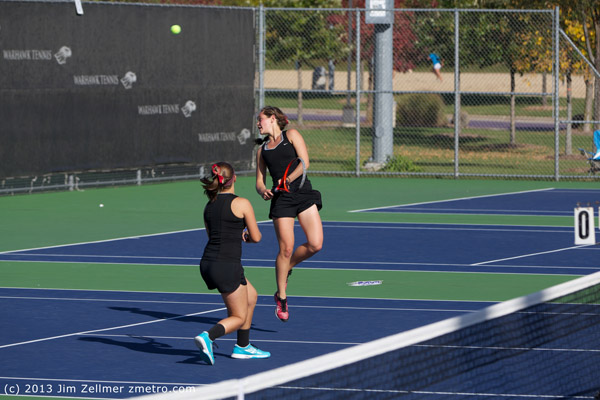

Lugging around a big, but excellent Canon zoom with the occasional extender offers its rewards. The images are sublime:

Yet, technology marches on, possibly leaving the incumbent camera manufacturers in the dust (Scroll down a bit to catch “Fake Chuck’s” worthwhile rant on smartphone competition).

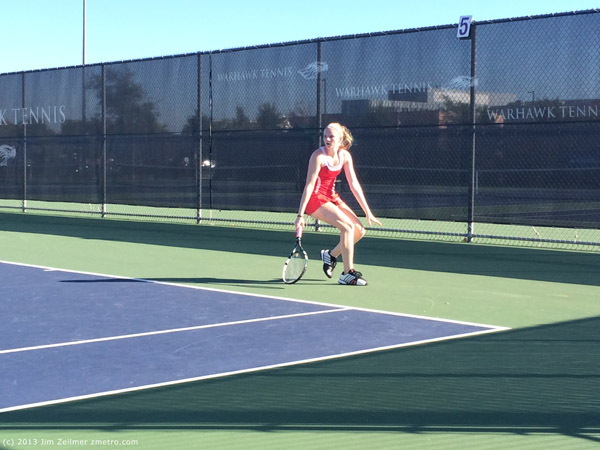

Apple has continued to improve the iPhone’s still and moving image capability. The photos are remarkable for such a small yet powerful computer. I recently had an opportunity to capture a number of outdoor tennis images with the new iPhone 5s (unlocked).

Lack of a big zoom requires quite a bit of moving around, something that is not always possible in an active sports venue.

Seated about 20 to 25 feet (6 to 7.6m) away from the players, I used the iPhone 5s’s camera app, digitally zoomed in and tried to focus on the moving player. I attempted to anticipate action. I then pressed and held the camera app’s shutter button. The iPhone 5s captures ten (!) frames per second in “burst mode”.

A few examples:

While the iPhone 5s will not completely supplant the big lens crowd, perhaps the next generation or two might. What software techniques might drive the next round of improvements? Three come to mind:

1. Focus Stacking. Focustwist app.

2. Lytro

3. Panoramic techniques used in combination with one and two above.

Next, a look at the Sony’s WiFi camera lens for iPhone and Android. A fascinating concept, though constrained by usability and battery issues.