Tap or click on the image to view the panoramic scene. Then pan in any direction.

Wikipedia and Turkey Travel Planner.

Pamukkale was a beautiful and relaxing stop on our recent trip through southwest and central Turkey along with Istanbul.

Monthly Archives: February 2013

Recipe for a perfect photo: clear sky, sunset and water

In 1861, the photographer Carleton E. Watkins hauled hundreds of pounds of camera equipment, sheets of glass and chemicals into Yosemite Valley in a darkroom wagon. For the first time, Mr. Watkins captured photographic images of these granite cliffs and waterfalls.

After seeing Mr. Watkins’s photographs, President Abraham Lincoln signed legislation in 1864 preserving the valley for the public and leading the way toward what would become the National Park Service.

In a strange coincidence, the molten effect of the sun on Horsetail Fall resembles another famous and highly photographed firefall here, one involving actual fire. Beginning around 1900, park workers collected Red Fir bark and built a large bonfire atop Glacier Point. After dark they pushed the red embers off the cliff in a cascade of glowing red coals, a must-see spectacle for the summer tourist set.

But in 1968, park officials ended the Yosemite Firefall, citing its man-made unnaturalness (the park banned feeding bears for the same reason). Five years later, the photographer and mountain climber Galen Rowell was driving through the park after a winter climb when he spotted the light catching in Horsetail Fall. He rushed across the valley and took what is believed to be the first image of the illuminated waterfall.

Mr. Rowell died in a plane crash in 2002, but his “Last Light on Horsetail Fall” remains the most well-known photograph of the apparition.

Why I’m quitting Facebook

Facebook is just such a technology. It does things on our behalf when we’re not even there. It actively misrepresents us to our friends, and worse misrepresents those who have befriended us to still others. To enable this dysfunctional situation — I call it “digiphrenia” — would be at the very least hypocritical. But to participate on Facebook as an author, in a way specifically intended to draw out the “likes” and resulting vulnerability of others, is untenable.

Facebook has never been merely a social platform. Rather, it exploits our social interactions the way a Tupperware party does.

Facebook does not exist to help us make friends, but to turn our network of connections, brand preferences and activities over time — our “social graphs” — into money for others.

We Facebook users have been building a treasure lode of big data that government and corporate researchers have been mining to predict and influence what we buy and for whom we vote. We have been handing over to them vast quantities of information about ourselves and our friends, loved ones and acquaintances. With this information, Facebook and the “big data” research firms purchasing their data predict still more things about us — from our future product purchases or sexual orientation to our likelihood for civil disobedience or even terrorism.

The true end users of Facebook are the marketers who want to reach and influence us. They are Facebook’s paying customers; we are the product. And we are its workers. The countless hours that we — and the young, particularly — spend on our profiles are the unpaid labor on which Facebook justifies its stock valuation.

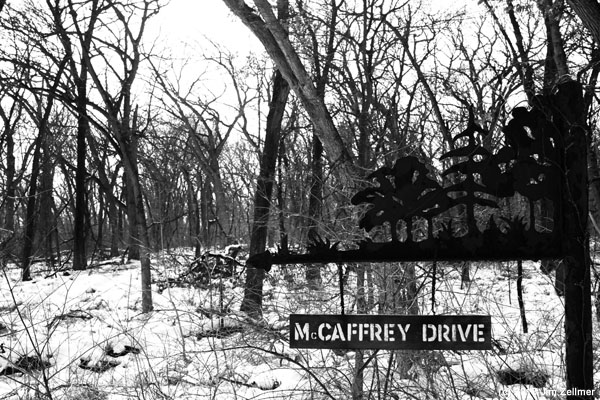

University of Wisconsin Arboretum: A few photos

Turkeys in the Arboretum

Do “Common Messages” save Money?

Why? Because auto manufacturers are confusing vehicle architecture symmetries – the use of fewer, common platforms for global manufacturing efficiency – with a delusional push for the commonality of brand image wrangling. They think a common message will save money. And, guess what? It rarely, if ever, works. Instead they spend more money unwinding campaigns that fall flat in regions around the world because they didn’t translate with the needed impact.

Now we have BMW marketers in Germany deciding that “Designed For Driving Pleasure” will be the new global ad theme for the brand, completely ignoring markets around the rest of the world, especially here in the USA where “The Ultimate Driving Machine” resonates with authority still. (I fully expect the powers that be at BMW to say that this new ad campaign will not replace “The Ultimate Driving Machine” in this country. But their credibility is more than a little suspect when it comes to such things.)

“Some technologies surely have an education role, but they are often, in my view, an answer in search of a question”

I was recently asked by a graduate student/author about this quote: “Some technologies surely have an education role, but they are often, in my view, an answer in search of a question.” (Jim Zellmer). I used this sentence in a weekly newsletter from my schoolinfosystem.org blog.

Pondering this question, I thought it might be useful to revisit the history of these words, at least in my experience.

I have used variants of this statement since co-founding an internet software firm in 1995. I referred to certain technologies, particularly during the dot-com era as “answers in search of questions”.

It is certainly possible that I heard this statement somewhere along the way. Perhaps others have used different words.

I attended a conference in the late 1990’s which featured entrepreneur Sam Zell.

Zell took questions after his talk.

A dot.com founder chastised him and firms like his “Equity Group” for not adopting their “innovative services”. Zell quickly shut them up by referring to most such products as “intellectual masturbation“.

I continue to believe that variations around “answers in search of a question” is a far better choice than Zell’s limited audience, but effective version.

Why speaking English can make you poor when you retire

Could the language we speak skew our financial decision-making, and does the fact that you’re reading this in English make you less likely than a Mandarin speaker to save for your old age?

It is a controversial theory which has been given some weight by new findings from a Yale University behavioural economist, Keith Chen.

Prof Chen says his research proves that the grammar of the language we speak affects both our finances and our health.

Bluntly, he says, if you speak English you are likely to save less for your old age, smoke more and get less exercise than if you speak a language like Mandarin, Yoruba or Malay.

On Cyberwar

A few years ago, Israeli and American intelligence developed a computer virus with a specific military objective: damaging Iranian nuclear facilities. Stuxnet was spread via USB sticks and settled silently on Windows PCs. From there it looked into networks for specific industrial centrifuges using Siemens SCADA control devices spinning at highspeed to seperate Uranium-235 (the bomb stuff) from Uranium-238 (the non-bomb stuff).

Iran, like many other countries, has a nuclear program for power generation and the production of isotopes for medical applications. Most countries buy the latter from specialists like the Netherlands that produces medical isotopes in a special reactor at ECN. The western boycott of Iran makes it impossible to purchase isotopes on the open market. Making them yourself is far from ideal, but the only option that remains as import blocked.

Why the boycott? Officially, according to the U.S. because Iran does not want to give sufficient openness about its weapons programs. In particular, military applications of nuclear program is an official source of concern. This concern is a fairly recent and for some reason has only been reactivated after the US attack on Iraq (a lot of the original nuclear equipment in Iran was supplied by American and German companies with funding from the World Bank before the 1979 revolution). The most curious of all allegations of Western governments about Iran is that they are never more than vague insinuations. When all 16 U.S. intelligence agencies in 2007 produced a joint study there was a clear conclusion: Iran is not developing a nuclear weapon (recent speech by the leader of this study here).

5 Ways GE Plays the Tax Game

General Electric’s tax department is famous for inventing ways to pay Uncle Sam less. So it should come as no surprise that its CEO, Jeff Immelt, is in the crosshairs as the new chairman of the President’s Council on Jobs and Competitiveness.

The job puts him in the limelight as Washington debates ways to make the tax system fairer, respond to competition from low tax countries and cut the federal deficit — competing imperatives sure to confound reform efforts. If the debate does get serious, attention is likely to focus on whether to get rid of some of the special tax advantages that benefit GE and other multinational companies.

Still, GE is in a class by itself. Here are five ways the company pares its tax rate well below the top U.S. corporate rate of 35 percent — sometimes into the single digits.

Strategy No. 1: The Tax Department as Profit Center

GE’s tax department is well known for its size, skill and hiring of former government officials. About 20 years ago, GE’s tax employees totaled a few hundred and were decentralized. Today, there are almost 1,000. The department’s strong suit? Reducing the taxes GE reports for earnings purposes.